A Free OSINT Lesson: Being a Defense Attorney is Hard

Or, How I Learned to Watch Really Old Surveillance Footage For a Criminal Case Using OSINT

To be a lawyer, you need to be a nerd. Lawyers nerd out on legal shit. Statutes, case law, and using phrases like “boiler plate” or “fruit of the poison tree.”

And while this isn’t a rule, most lawyers I know aren’t nerds the way that I am. Now, I don’t mean my love of science fiction and really cheesy fantasy novels. I mean the digital side of being a nerd. The hours I spent as a teenager trying to download cheats for Team Fortress Classic so I could run an ‘aim bot,’ or downloading mods for Deus Ex. Even as a grown ass man with three kids, I still took four hours to find the perfect balance of graphics settings to run Cyberpunk 2077 on my gaming PC. I wanted to achieve that perfect mix of performance and graphics, running checks on my frame rate and GPU temperature, so everything looked super dope but never stuttered. I literally read forum posts on how to push my graphics card to the limit without cooking it, and how to maintain stability so the game didn’t crash. It’s a bit pathetic in hindsight, and most lawyers I know don’t have time for that kind of shit.

At Permanent Record Research, we primarily work with lawyers who specialize in wrongful conviction cases and indigent defence. It’s a bit of a mixed bag, and I’ve learned some pretty hard truths. As a kid who grew up watching Law & Order in the early 90s, the last 18 months have been one big existential crisis. We’ve bumped into multiple cases where digital evidence was misused, misinterpreted, or just totally fucked up by law enforcement.

That never happens on TV.

In a fairly recent appeal case we’ve taken on, our client provided us a massive dump of video files that were recorded back in 2014 and 2015.

Now, a fun truth people often share is that only two things are certain: death and taxes—if I had to add a third, software changes (Oh, and that no one exports shit properly, but that is for another time).

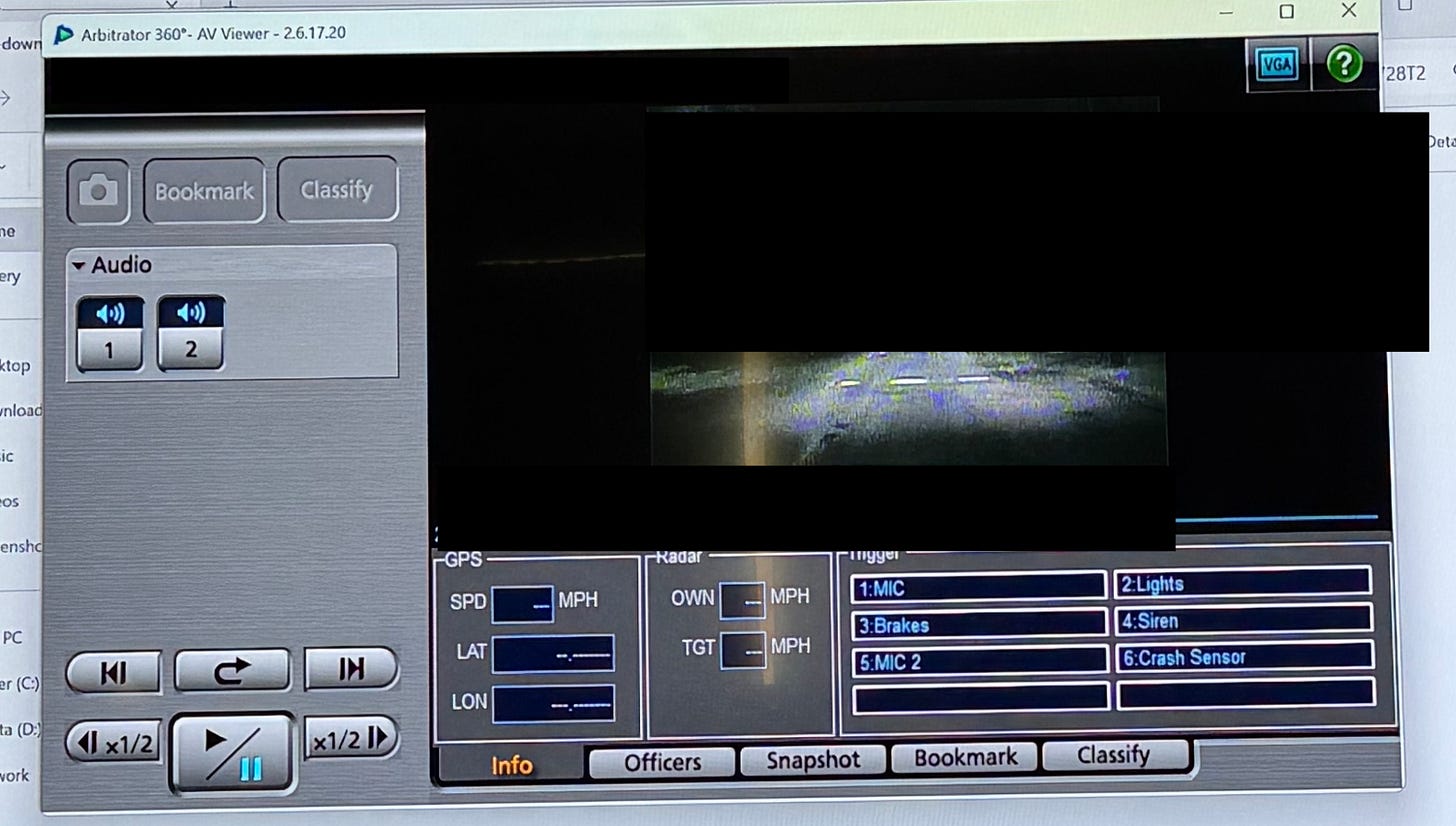

One set of video files for this case involved police dashcam footage shot on a decade-old system made by Panasonic called “Arbitrator.” Panasonic actually stopped selling this system a while back, and it’s been handed over to a company whose name sounds like they make knock-off AirPods called “i-Pro.” I digress.

This system would pump out video files in a “.av” format, and encrypt the shit out of it for security reasons, and so no other system could play them. In simple terms, you want to watch the .av file, you need Panasonic’s proprietary software.

Now, when the video files were sent along in the discovery package to our client, they were all packaged in a digital folder, disorganized, and in a giant mess of various file types with no real clarity as to what was what. It was an anxiety-inducing collection of dozens and dozens of .dll, .inf, .ax, .xml, .ocx, .bat, and .manifest files, all kinda crammed in with a few .exe and .av files.

Now, to make things more interesting, there was a whole second series of videos from a totally different and even older surveillance system called “Quickwave” which comes with .60h and .60d files.

Now, did anyone from the District Attorney’s office or from the police department leave instructions for any of this? A simple “ReadMe” file?

Hell no.

There were a few useless PDFs from 2016 on how to use the software once you got it loaded, but nothing on where actually to get it… you know… since they fucking stopped making it.

The fact of the matter is that lawyers who work in public defence don’t just work one case at a time. They work dozens of them. The thought of obtaining folders like this for multiple cases, containing video files that can’t be opened, from systems that are no longer in use or even exist, well, it makes my bowels loosen.

For nerds like us at Permanent Record, it took us a bit of time to figure out what went where and with what. For a lawyer with no background in this, it could have been written in an alien language from some distant world.

When we finally got it all parsed out and organized, the next hurdle appeared. How exactly do you run this? We knew that the AV_Viewer.exe file was the actual tool, and that the .av file was the footage we needed, but simply downloading and trying to install the AV Viewer program didn’t work. It kept bumping into errors and just wouldn’t load.

From here, I turned to the best place to find both useful and useless information. Reddit.

I can’t overstate the importance of Reddit to OSINT and the investigation field. It’s like the Mos Eisley spaceport in Star Wars, full of scum and villainy, but it's also where Han Solo and Chewie hang out when you need a ride to Aldera

I found multiple posts about AV Viewer, and the general frustration people experience in trying to open .av files.

There were multiple posts about how to use VLC to open .AV files, and small tweaks you can make to the software. However, there was one big hitch in my situation.

Law enforcement .av files have specific codecs from Panasonic that come with this system. So, either I have them and don’t know it, or they weren’t sent along with the discovery.

It was at this moment that I had a dark and conspiratorial thought. Why was all this just dumped into a discovery file with no rhyme or reason? Was it meant to be purposefully confusing and difficult? For a police video forensics expert, this would all make sense. But for a lawyer who nerds out on case law, not archaic video files, this would be a nearly impossible task.

So was this malice? A purposeful attempt to keep this all so complicated that an overworked and underpaid public defence lawyer would never be able to open those video files? Or was this simply apathy on the part of the prosecution? Fair trials be damned?

I decided to download all the files sent over, assuming they were part of the AV Viewer software. Basically, the .exe file and the various configuration files that I could only assume came with the program, and tossed them into one folder on my Desktop. There were a dozen or so.

I double-clicked the .av file.

And it opened the software!

But then it said the file couldn’t be played.

Damn it!

Now, this bit here is the dope free lesson you’ve come to expect from good ol’ MJ. If you’ve not seen recent posts from my esteemed colleague Justin Seitz, he recently highlighted a search engine called “Kagi.”

For all that is good and holy in this world, every investigator and OSINTer needs to download Kagi. This thing is what search engines were like before they were “enshitified” by the tech bros we assumed would save us back in the late nineties and early aughts. You get 100 free searches, and if you want more, it’s like $5/month. For the sake of transparency, I am a paying customer of Kagi, and this is not a sponsored post or anything of the sort. They have no idea I’m doing this. It is that good of a search engine.

To sum up, we have all the files organized. We know what files are video files. We are trying to sort out why the version of AV Viewer sent over by law enforcement isn’t working.

I cracked open a Coke Zero (nope, still not being sponsored by them) and took down a massive swallow of the potion. Like Geralt of Rivia, my eyes dilated, and I was filled with the strength of ten investigators.

I turned to the chaos-causing power of Kagi and said, “I can’t be the only person hunting this monster. Somewhere this must exist! Someone has been down this road before…”

I punched in “Playing .av AV Viewer” and then set it to give me any PDF results regarding this software.

And the very first hit was an old 2014 PDF from the Montgomery County State’s Attorney’s Office. It was an instruction manual for defence attorneys on how to access various pieces of the state’s evidence. Section 2 is about Panasonic Arbitrator .AV videos. And… amazingly… there was a Google Drive link to the software itself, along with the proper codecs.

No fuckin way…

The Montgomery County folder only contained three items for the player. The .exe, a codec for playing the video, and an ActiveX file that lets the video actually play.

So I followed their instructions, downloaded the files, and then tried to play the video.

Success!

Another good resource I found was DME Resources, created by Larry Compton. He has a whole host of various video and digital forensics tools, both new and old, on his site, and some helpful blog posts about how to use them. I did poke around his site for some other tools I needed for this case, and it was very helpful.

As a test, I pulled those three specific file items listed in the Montgomery County document from the discovery folder we had and separated them from the rest. Interestingly, the .av file played.

So, something else in the discovery mess was causing a conflict. I have yet to ascertain what.

Regardless, I’m still dealing with that sense of conspiratorial dread. This file dump from the prosecution side was an interesting lesson. Being able to access files with possible exculpatory evidence seems like an essential part of a fair justice system. Is it enough for the digital forensic nerds working for law enforcement to simply drop it in the lap of a lawyer and say, “You figure this shit out.” The parties here aren’t matched in diverse knowledge bases, time, or money. A lawyer working in indigent defence may not have the resources to access experts to go through this, or the time, as they juggle their case loads.

I’m not a lawyer, but I know how to be an asshole. Whether dumping a disorganized mess of digital forensics data on a lawyer was purposeful or just apathy, that is very much the work of an asshole.