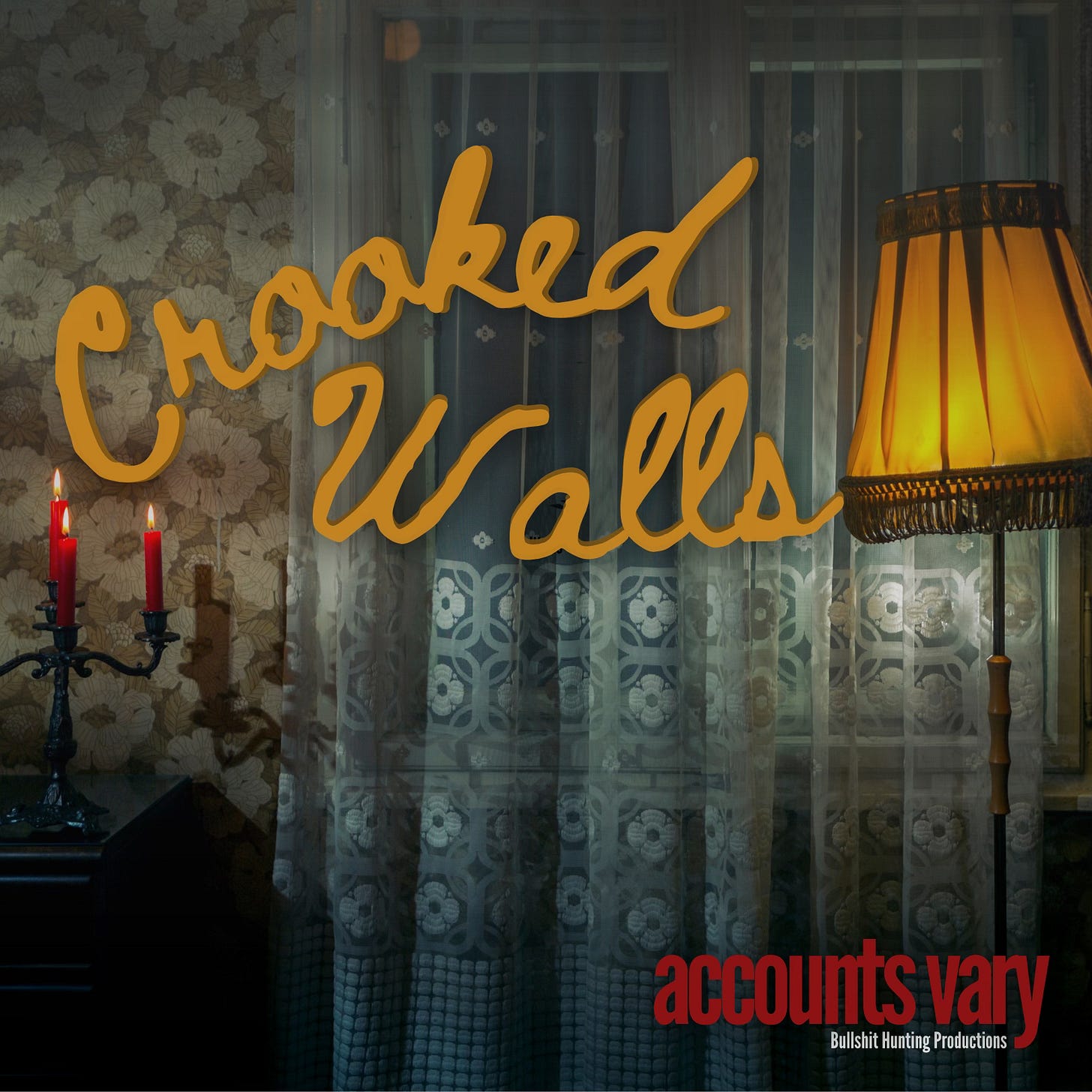

Crooked Walls I

Chapter 1: Moving In, Moving Backward

Eva had promised herself she would not become one of those people who bought a century-old house and then immediately complained when it acted like one.

The first morning in the Victorian, she woke before her alarm with the light coming in softly through the stained-glass windows. The air didn’t quite smell like hers yet, more a faint scent of cut wood and cardboard, perhaps the boxes she’d broken down the night before and stacked neatly by the back door. Pipes pinged somewhere in the walls, the heat coming on with a gentle metallic sigh. She stretched and smiled at the high plaster ceiling and thought to herself, I did it.

As she went into the kitchen, the floors announced her in a few precise notes: one near the threshold to the dining room, two beside the built-in hutch. She noted everything in its newness. The counters were old maple, oiled to a glow; she’d run her palm over them when she toured and felt inexplicably protective.

She found the mug she loved, heavy white diner ceramic, a souvenir from a roadside place she’d stopped at once, and poured her coffee. Steam rode past her face and the chill at her ankles moved away. Dust drifted in the slant of light as she thought again, satisfied, I did it.

The plan for the day was gentle: unbox the kitchen, hang a curtain rod in the front room, and send her sister a link to the listing so they could laugh one last time at the “before” photos—the rose-print wallpaper, the staged bowl of lemons, the tiny lamp with the shade askew. Online, everything looked like everything else. Every living room had the same grey sectional; every kitchen had the same IKEA succulents lined up on the windowsill. But this house didn’t. Its woodwork was unapologetically dark, its staircase turn was abrupt and theatrical, the doors were far too heavy, and that’s why she loved it.

She opened the laptop on the little oak table that had been her grandmother’s and typed the address into Zillow. The page took a second to load and then popped into place. There it was: the listing she’d memorized, the carousel of photos she’d exhausted herself looking at. She clicked the first image, waiting for the familiar front porch with its gingerbread trim and bay window to the right of the front door.

As the porch appeared, she saw the same trim and a bay window—on the left.

Eva clicked forward, then back. The second photo showed the living room. Same chandelier with frosted tulip shades, but the staircase rose from the left-hand wall instead of the right. She blinked and leaned closer.

It didn’t make a lot of sense that new photos would be appearing at this point, but they had to be. Mirror images. She’d seen real estate photographers do odd things with wide-angle lenses and editing. Mirrors could flip interiors; some apps auto-corrected orientation based on the phone and got confused. It was a thing, and a mundane explanation.

She clicked the “Price/Tax History” grounding herself in the numeric and the bland. The box dropped down obediently, showing dates and dollar figures she already knew: listed last year, price cut in fall, sold this fall. Beneath that, “Public Facts”—square footage, lot size, number of bathrooms. Zillow had saved three sets of photos under “Listing History,” the way it often did: two years ago, one year ago, six months ago.

The six-month set was the one she remembered; it was how she’d fallen for the house in the first place. She clicked it and blinked again. The kitchen cabinets were flipped. Handles on the left, hinges on the right. The fridge was on the opposite wall. The little scuff on the floor where she’d noticed a board had lifted slightly—gone. Instead, a clean rectangle of wood where her real life had a blemish.

Eva laughed once—thin, but genuine—and opened a new tab. Realtor.com. Different photos; similar wrongness. The living room photo here showed the bay window correctly but the throw rug was on the other side. The fireplace mantel was hung with three framed black-and-white photos. She zoomed in and squinted at the blurred faces. They must’ve staged the home at some point, put props in.

She closed the tab.

The county assessor would settle it. Assessor sketches were unromantic little diagrams in black-and-white, more honest than a real estate listing. She found the property search portal, typed in her address, scrolled past the tax roll and land use codes, and clicked “Building Details.”

The sketch loaded slowly. First floor: living room, dining room, kitchen. A rectangle labeled “FP” where the fireplace sat. A run of small squares along the right-hand edge, the stairs.

A creak came from the kitchen, grabbing her attention, and when she turned back, the lines had rearranged themselves, or her brain did, and she saw it: the stair squares weren’t along the right-hand edge. They were on the left.

The black lines seemed to float on the white, nearly shimmying the way your eyes with an optical-illusion. She refreshed the page. The same. She tried the property card PDF. The older one matched the new one: stairs on the left. She pinched the bridge of her nose and reminded herself that none of this was reality.

It was representations of reality, which were always approximate. What she was seeing, here, now, was reality.

Fine. She took a pencil to the back of an envelope and made a box, writing “TO CHECK” along the top. Beneath it, in small exact letters, she wrote:

Wayback Zillow/Realtor (older snapshots)

Assessor parcel history (APN chain)

Sanborn fire maps (2.5 stories?)

Street View history (porch orientation)

Permit history (remodels, chimneys)

MLS # (params in URL if cached)

The list itself calmed her. If you can enumerate a thing, you can hold it.

She started with the Wayback Machine. Zillow pages were sometimes captured haphazardly—photos broken, JavaScript not loading—but she plugged the listing URL into the search and, to her surprise, got a nice little timeline of blue hashes. She clicked a snapshot from eleven months ago. The gallery opened with the same mirrored kitchen. She clicked one from two years ago and got a different set entirely with a family’s furniture, toys scattered under the bay window, a piano against the wall. The staircase in those photos was unequivocally on the left.

She scrolled and noticed the URL included a string after the address: MLS=1103842. She copied it. On Realtor.com, a similar string. Different numbers. She opened a new tab and put the MLS number into a Google search with quotation marks. A small cache of real estate aggregator sites she didn’t recognize popped up, all with dead thumbnails and the same minimal text: 3 bed, 2 bath, 2,080 sq ft, built 1908.

She saved the pages as PDFs anyway.

There was a good chance the interior photos she’d been given during the purchase had been from a listing that was never actually live on Zillow. Agents moved images around, pulled them, replaced them. More likely, the photographer had used an editing tool that mirrored a few to make the composition feel more balanced. If she called the agent, she could probably confirm that in two minutes..

But she turned to the physical house—the only record that mattered, really—and walked it slowly with her coffee in one hand and a tape measure in the other. The living room’s bay window was shallower than it appeared in any of the photos; she measured from the front wall to the inside corner and wrote it down. The fireplace brick had a hairline crack she hadn’t noticed before, a faint zigzag. The trim on the doorway into the dining room had a nick at hip height that caught her sweater as she passed.

In the dining room, the built-in hutch was original. She ran a finger along the wavy glass and felt a prickle of pride that she would not have a home that had been stripped of its bones and draped with neutrals. She’d keep this wood dark. She’d polish it. She’d let the house be itself.

She measured from the front wall to the foot of the stairs and wrote it down. From the bottom step to the back wall. From the width of the hallway to the inside edge of the stairs. When she sketched these into her little plan, the right-sided version looked clean, true, proportionate.

The left-sided one looked true, too.

It was early afternoon by the time she opened the library’s digital portal and navigated the labyrinth into the Sanborn maps. She typed in her city and narrowed the date to 1924. The map tiles loaded in yellow and pink, parcels labeled with neat black numbers and shorthand annotations. She found her block, counted from the corner, and set her finger on her house. D for dwelling. 2½ for the stories. That half, she thought, would be the little attic.

The house was shaped like a fat rectangle that, compared to its neighbours, looked like two narrower houses pressed together. The porch was indicated with a thin line on what the map deemed the “east” side.

She switched to 1942. The footprint, which was the shape of the house, had changed; the rectangle was longer. The porch line had shifted. She checked the legend to make sure she wasn’t misreading a symbol. She was not.

Before she closed the tab, she saved both maps and wrote the file names into her notebook.

Street View felt like cheating but it was useful. She typed her address into Google Maps and clicked the little timeline on the left side of the imagery window. The oldest capture was 2008. The porch railings in that year were a simple crisscross pattern she didn’t have now; in later years, they were turned into spindles. In 2014, the image wobbled as if the car had hit a pothole; the porch looked skewed, but she suspected that was geometry, not physics. In 2018, she tapped further down the block so she could see her house from a sharper angle. The bay window looked deeper, but the later 2022 shot made it look shallow again.

She toggled back and forth until she felt seasick and closed it.

She opened the original six-month-old photos she’d been sent when she made the offer. They were in her email as attachments, labeled with a generic run of numbers. She downloaded them and right-clicked to get info. The metadata was tidy: taken on a Canon DSLR, mid-morning, March. She flipped to the next shot. Same. She dragged one into a little EXIF viewer and the fields were clean. Orientation: 1 (Normal). No sign of any mirrored processing.

It could all be some sort of glitch. It could all be easily explained.

She sent the listing link to her sister with a string of celebratory emojis and a note that said, Look how small it looked! You should see it now. I swear the rooms grew overnight.

Her sister messaged a minute later: Obsessed. That bay window! The layout seems different than I remember, but I love it!

Eva typed, Photographer probably mirrored something. Anyway, come over next weekend and bring croissants.

She set the phone down and breathed, long and deliberate. In for four, hold for seven, out for eight. The breath steadied in her chest. She had real things to do. Hooks to install. A curtain rod to hang.

The curtain rod fought her—old plaster, crumbly behind the paint. She cursed softly and then laughed at herself and the sound went up into the high corners of the room and came back warmer. She hung the curtains. The light softened and the house sighed.

By the evening, the boxes were fewer, the counters clear, the sink shining. The sun slid sideways across the living room floor, and Eva stood in the doorway and, for a small luxurious moment, imagined what it would be like to host here, to fill the room with voices and hands and the clink of glasses. She pictured the bay window in winter, a chair there with a blanket, a book in her lap, snow falling.

“Very boring,” she said to the house, pleased. “We’re going to be very boring, you and I.”

She turned off lights as she went upstairs, switch by switch, and at the top of the stairs her shoulder brushed the carved oak frame of the built-in mirror. She glanced the way people always do, a habit as much as vanity, and for one fractional second she saw the staircase behind her on the other side.

She stopped dead with her foot still hovering over the top step, her body’s balance arguing with her brain. Of course the staircase looked flipped in a mirror. That was how mirrors worked. What else should it do? The thought embarrassed her, and she breathed out a laugh that didn’t quite land.

The bathroom was a hodgepodge of at least three eras: hex tile floor, 1980s vanity, perfectly weighted old door that clicked shut like a safe. She washed her face. The mirror above the sink—different from the hall mirror, smaller and rectangular—was too close for any tricks of architecture. It gave her back the tired face of a woman who had moved in under forty-eight hours.

In bed, under a thick quilt, she put her phone face-down on the nightstand. The radiator ticked. Somewhere, a pipe settled. She fell asleep with the sensation of the floorboards mapping themselves under her again, another layer of the house learning her weight.

Sometime after midnight the wind came up and a sound, a soft, deliberate creak, woke her. She lay still and counted. One creak, two, silence. She was aware of the precise path those notes would trace if they were hers: across the landing, past the built-in mirror, down three steps to the mid-landing, then the long run to the first floor.

She told herself an old house with a new person made its own music.

In the morning, the sunlight painted the wall in honey and sea. She made coffee and it tasted a little like victory and a little like a dare.

Before she opened the laptop, she set a small ritual for herself—two rules: first, she would go and put her own eyes on the things the documents claimed. Second, she would not let representation outrun the real.

Zillow, first, just to check. The photos had not changed. Realtor, next; no change. She typed the parcel number into the assessor site, the one she’d copied last night in tiny neat print under “APN.” A new field caught her eye—“Prior Parcel Number.” She clicked the little arrow beside it and saw a chain of numbers, each linked to a previous lot configuration. She followed it back: 2003, 1989, 1974. In 1974, the parcel was two. In 1989, merged. She wrote it down and allowed herself a small hum of satisfaction. Two made one. The house had been itself and also its sibling.

She put the address into a general search and clicked “Images,” expecting the same staged lemons. Mixed in were a few unfamiliar angles: a low, moody shot from the side yard; a night photo taken from the sidewalk with the porch light on and moths orbiting. She clicked that one. It opened to a small neighborhood blog. The caption read, “Our old place, 2019.” She scrolled. The post beneath captured simple memories, the author’s child learning to climb the stairs by sitting and scooting, the sound the screen door made, the way “the bay held winter light like a bowl.”

The author had listed small details with painstaking adoration: the third stair from the bottom that squeaked less if you stepped on the outside edge, the nail you had to push with your thumb before the back closet would latch, the tiny scorch mark on the kitchen counter.

Eva went to the kitchen and found the scorch mark exactly as described, two millimetres wide.

On the way back to the table she paused at the bottom of the stairs and put her foot on the third step from the bottom and pressed down on the outer edge. The squeak was gentler there. She felt unreasonably grateful, like being handed instructions to a stubborn machine.

In the late afternoon she walked to the end of the block and back, just to taste the air. A neighbour waved from a porch, the wind moved gently through the maples. When she returned and climbed her steps, she noticed a small thing she hadn’t before: the porch boards ran north-south, not east-west. In the Zillow photo, she could have sworn they ran east-west. She crouched and peered along the seams. They were, unmistakably, north-south.

She took a picture of her own porch floor and then screenshot the photo from Zillow. Looking at them side by side, she felt foolish because yes, in one the boards ran east-west, and in the other they did not, and nothing about that meant the house was not being a house.

She made tea. She salted the front steps because the forecast threatened a freeze overnight. She put the boxes out by the bins and came back inside, locked the door and felt pleased when the deadbolt slid home.

Evening settled into the rooms, and in bed she checked her sister’s text—Next weekend. Croissants. Eva responded with a photo of the bay window.

The radiator ticked. A car passed far off with a soft swish. Her breath evened. Sleep came, ordinary, welcome, and deserved.

At some hour that had no name, the house made the sound again: a soft, deliberate creak across the landing, not loud enough to be footsteps and not random enough to be wind. She woke all at once, eyes open to the dark, and lay there with her heart counting out an old pattern, conscious of the map she could draw without light: three steps to the door, five to the hall, eight to the top of the stairs. The dark softened and the sound thinned and the house breathed with her again.

When she slept, she dreamed of drawings. Thin black lines on white folding and unfolding along a seam she could not see. In the dream, both versions were accurate and neither was faithful.

She went downstairs by the path her body had already learned and put her hand on the stair post, feeling the nick where it would always be.

Right where she remembered it.

For now.