Strange Love Game - Chapter Three

The Crossfire Gambit

Chapter three in our series A Strange Love game - read Chapter Two here.

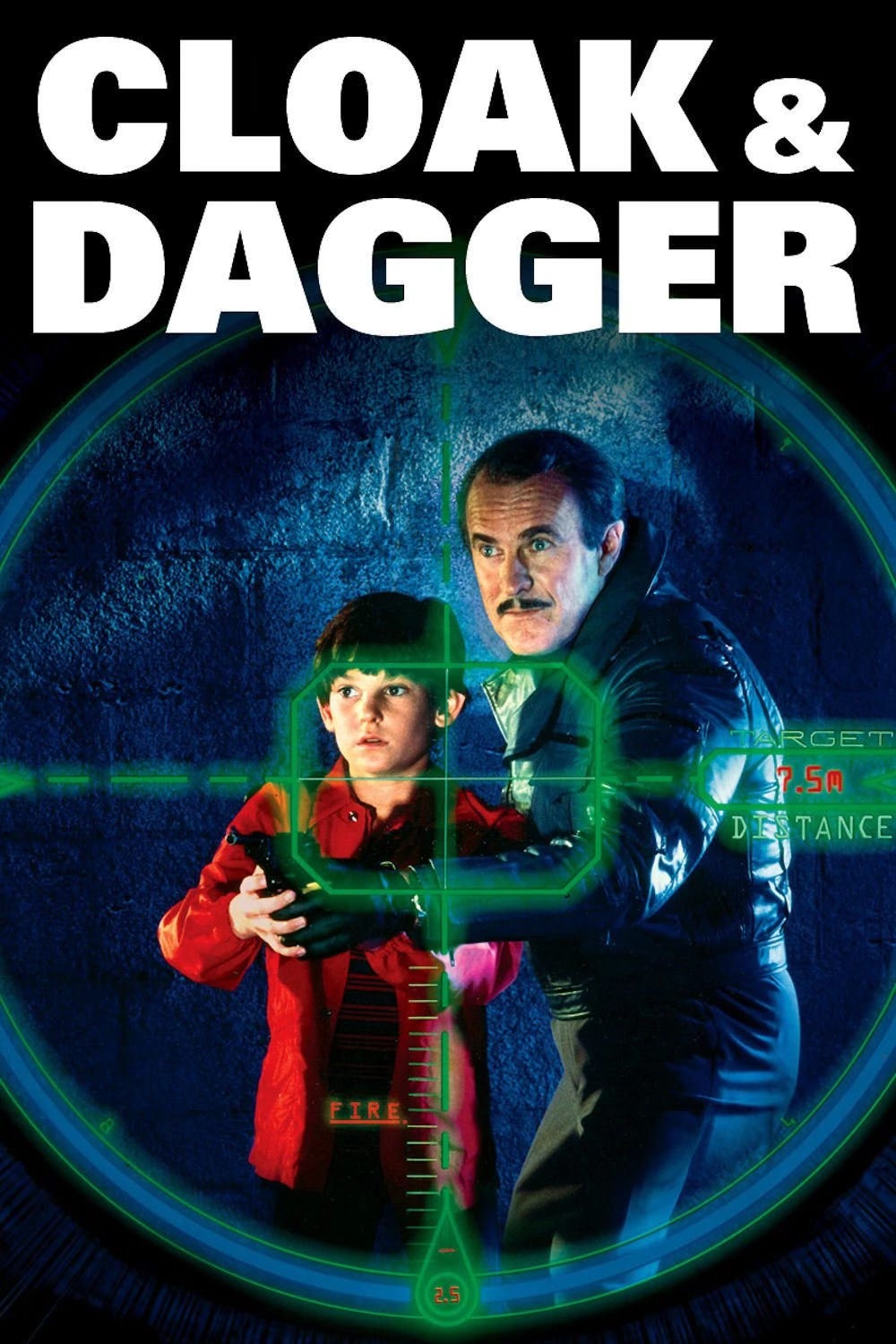

When I first searched for "CROSSFIRE GAMBIT" alongside the usual military bases, naval vessels, and covert operation codenames, I came up with a whole lot of nothing. No secret files, no Cold War archives. Just crickets. The only reference I found was to an old 1984 spy movie called Cloak & Dagger. It’s funny how life loops back sometimes—our very own MJ Banias hosted a podcast under that same title in a previous life, and Kennedy may have had an episode or two on that same program.

From the Wikipedia page, I spotted the following:

11-year-old Davey Osborne lives in San Antonio, Texas. His father, Hal, is a military air traffic controller who has problems relating to Davey, moreso in the wake of the death of Davey's mom/Hal's wife. ... During the ensuing fight, Jack urges Davey to lure two spies into the "Crossfire Gambit," causing one to kill the other.

Ok, so, Cloak & Dagger is set in San Antonio, Texas—the first three digits of the GrayBeat audio clues are the area code "726.” I had already purchased a copy of the movie to rewatch at my leisure and scrutinize for potential clues.

No time like the present to get it playing.

I click play, minimize the video window and while it starts in the background, turn my attention to the poetry on the front of the tear sheet.

"I made up my mind to come and live with you here in the Night Land."

The first result on Google was a Cherokee poem, which immediately gave me pause. Relying on a translated Cherokee text was a bold move, even for an ARG. Translations, especially from Indigenous languages, are notoriously tricky. Still, I couldn’t ignore the significance. Cherokee culture has a deep and storied history in coded communications, so this could easily be another subtle clue.

Most people think of the Navajo code talkers from World War II—popularized by the 2002 film Windtalkers, starring Nicolas Cage—but the Cherokee were actually the pioneers. According to the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources:

The Cherokee “code talkers” were the first known use of Native Americans in the American military to transmit messages under fire, and they continued to serve in this unique capacity for rest of World War I. Their success was part of the inspiration for the better-known use of Navajo code talkers during World War II.

Cherokee Code Talkers and Allied Success in WWI, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, August 21, 2016. Accessed July 29, 15:16CT.

With the Cherokee angle in mind, I moved past the translations and stumbled upon something else: The Night Land, a horror story by William Hope Hodgson, published in 1912. Admittedly, as a self-proclaimed uncultured North Asscheek-dweller, I’d never heard of it before. But as I paged through reviews and snippets of the text, I couldn’t shake the feeling that Hodgson was leading me somewhere—like his words were more than just fiction but coded instructions.

Now, as I went towards the North and West, I steered me warily for a great while, that I come safe of that Great Watcher of the North-West.

Then I came out of the water, and went forward, stooping and creeping, among the moss-bushes, going outward to the Westward of North, so that I should go away so quickly as I might from the nearness of the House.

—The Night Land, William Hope Hodgson, 1912.

While reading Hodgson’s cryptic prose, a memory sparked. Poetry, after all, has played a role in real-world treasure hunts, and not all of them ended well. Some treasure seekers never returned alive, something I’d learned through countless podcasts over the years.

One particularly infamous treasure hunt came to mind: in 2010, art dealer Forrest Fenn of Santa Fe, New Mexico, published a memoir titled The Thrill of the Chase. Hidden within its pages was a poem containing nine clues to a fortune of gold and jewels he claimed to have buried somewhere in the Rocky Mountains. It triggered a modern-day gold rush, attracting podcasters, journalists, and countless treasure hunters who obsessed over every word, every line break, hoping to decode the clues and strike rich.

As the years passed, speculation grew that this was a hoax or simply, the treasure would never be found. Until 2020, when a Michigan medical student, Jack Stuef, claimed the fortune and kissed his student loan debt goodbye—fuck yeah, Jack.

It felt like The Night Land was harkening to the buried treasure of Forest Fenn, whether the Dungeon Master of the So Joana mystery had intended it that way or not.

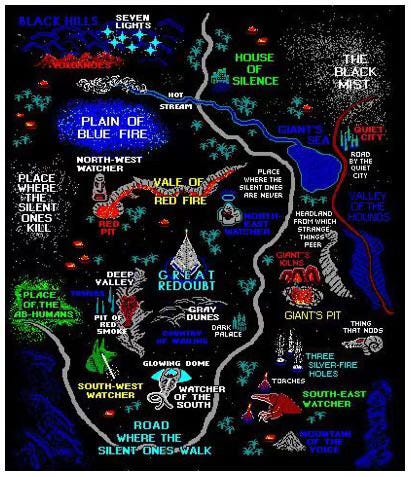

Soon enough, I discover yet another Reddit thread, this time on /r/WeirdLit by SilentMotorist, where they say they adore a map of The Night Land by Hodgson. It looks like an 8-bit rendering of a map that one would find in a 1980s video game. It’s awesome.

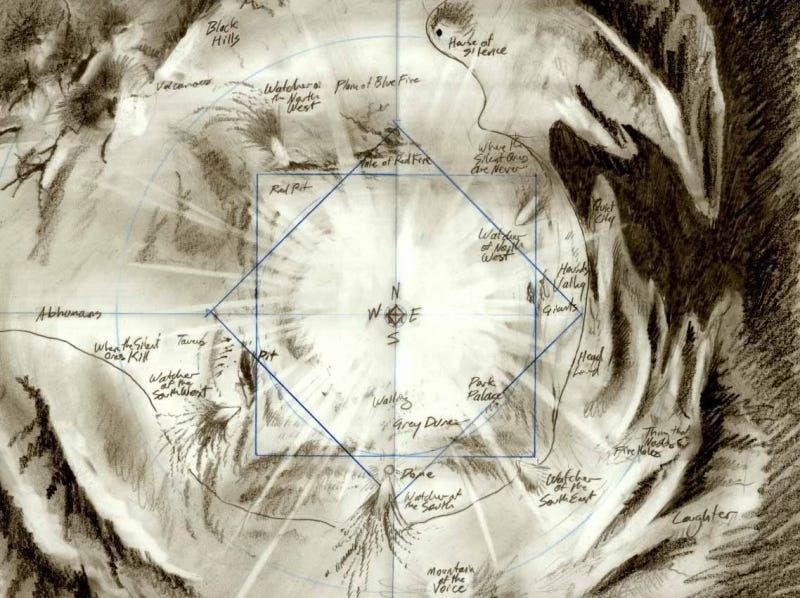

The entire vibe of treasure hunting, deciphering maps, and immersing myself in this alternate reality game had me poring over countless interpretations of Hodgson's work. It turns out that The Night Land has inspired a niche subculture of readers who create and share maps based on how they envision the eerie landscapes from the story. As I continued exploring, I stumbled upon a beautifully hand-drawn map by Brett Davidson, which immediately caught my attention.

Something about it stopped me cold. Maybe it was the intricate pen drawings layered on top, or maybe I’d just been staring at too many clues for too long, but it looked off. Like there was more to it than met the eye.

I printed out the map, laid it on my kitchen table, and began rotating it. That’s when it hit me: upside down, the center of the map looked like an explosion—like the view from above a blast’s epicenter.

“Wait a second,” I muttered to myself. “Could this be pointing to some kind of explosion in San Antonio?”

I scratched Esme’s chin while I thought it over. She playfully bit my finger, irritated that I’d left her earlier.

I pulled up Google again and typed in “San Antonio explosion.” What I found made me grin.

“No way,” I said, chuckling as I rubbed the spot where Esme nipped me. “I certainly don’t remember that time a nuclear weapons bunker blew up in San Antonio.”

Esme remained unimpressed, flopping as if to say, “These humans and their games,” with an eye roll.

But I felt the rush. The map, the explosion, the Cherokee connection, Hodgson’s cryptic directions—these random threads, all tied together somehow. Right now, I didn’t care if there was a prize waiting at the end. This was the thrill.

Esme gave me a look of deep skepticism.

She bit me once more. Clearly, I’d been gone too long.

Continue reading Chapter Four.

This is a good hit or couple of hits of dopamine.