Time Cop: Wrangling Disordered Digital Evidence

Time synchronization techniques when your digital media gets unruly.

I imagine the 9-1-1 operator listening intently.

"Did you hear it? Did you hear that?"

The pleading voice came from a small family-operated corner store in the north end of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

"This happens every day, and I want someone to do something about it," the voice squeaked out, now an octave higher, but tone hushed.

The 9-1-1 operator, furiously taking shorthand notes into the computer-aided dispatch software, suddenly stopped mid-keystroke and snapped their head up.

"I did hear that, ma’am," the operator said, stunned, "uhh, is he threatening you in any way, or is he armed?"

"Not that I can see. But usually, he says, 'pick the bones out of that one', whatever that means, and then he leaves, and” the shopkeeper paused over the jingling of the bells of the door, signalling the culprit's exit, "I really think it's a threat."

The last statement was too much for the operator, and what little professionalism they possessed eroded instantly as they slapped the mute button on their headset and erupted into laughter.

The sound the complainant was referring to was a raucous fart. The phrase, 'pick the bones of that one', muttered under the breath of an unidentified, geriatric rogue, was a Prairie-dwellers' way of saying: get a load of this enormous expression of flatulence.

Enjoy it. Breathe it in.

There may also be a reference to the smell of a dead carcass layered in there somewhere, implying the carcass is no longer anything but a pile of bones. Either way. It's fucking funny.

Wheezing, snorting, and torso-twisting so furiously that the ordeal made the Staples office chair creak to the same beat. Feet stamping into the ground as though on fire, the emergency responder had little time to let it all out before the caller reminded them they were very much still on the line. And this? An emergency.

"Hello?" the voice could be heard, a note of annoyance in their tone.

Recovering, the operator quickly responded, "Excuse me," while wiping snot and tears away, "Yes, ma'am, I've entered your complaint, and please do call back if the man threatens you or you feel unsafe."

And so concludes the 5-minute 9-1-1 audio in this case. Beside it in the discovery folder is an hour-long video clip, without audio, and without any date or timestamps. In this video, one can see an elderly man entering the small convenience store, not purchasing anything, pausing briefly to pump one arm and cock a leg, before leaving. You can imagine this is when the air cannon was deployed from the rear deck of the admiral’s pants, but you can’t hear it; you can only see it—well, sort of. You can’t really see a fart, but I’m not here to plead his innocence.

As the culprit hits the doorway, he gives three swift backstrokes with his right hand. One can only assume this maneuver is to push the malodorous cloud deeper into the store, trapping it inside. The man then leaves, with the jingling bells heard in the 9-1-1 call, now visually shown bouncing against the door.

It is now your job to take the 9-1-1 audio and synchronize it with the soundless video of the old man to join the two together. So that you can both see and hear, but thankfully, not smell, what is going on.

Sadly, this is a fictional case, but the underlying problem is very real.

A Universal Discovery Problem

In many modern criminal justice investigations, whether you’re a prosecutor, a defense attorney or a journalist, you are going to be dealing with a handful of common pieces of evidence. In most cases, you will have a PDF of the relevant investigative notes, warrants, and other information (journalists usually don’t get all of this) and then a handful of common digital media: body-worn camera footage, 9-1-1 call audio, and frequently, surveillance footage and digital forensic evidence to go with it.

All of these bits and pieces of video, audio, and digital cruft are extremely useful when putting together your case timeline. Yet, under this sea of data lies a silent monster slithering in your discovery: time synchronization.

Few of the digital materials you will collect will be from the same source, which means you need to figure out how to synchronize two totally different pieces of media to the same clock.

The Case of the Farting Man is a perfect example where we have one source of evidence that provides a time stamp but no video (this is the 9-1-1 call), and another source that may have video but no audio or a reliable date and time (the security camera footage). This problem can repeat itself in a variety of combinations and permutations, varying only in how much digital evidence you might be dealing with.

To synchronize media sources, we first need to spend a little time breaking down and documenting the evidence. Then we can add a pinch of napkin math to solve it. The goal is to learn tactics and techniques; there is no silver bullet in investigative or analytical work. Let’s get cracking.

Step 1: Find a Media Source with a Date and Timestamp

In many cases, you will have at least one source of evidence that has a timestamp of some kind. For example, in our case, the 9-1-1 audio will have the precise time the call was connected, and this can be corroborated from both the computer system at the emergency dispatch center and the phone records of the caller.

This makes the 9-1-1 call an ideal candidate to find an anchor point from which we can synchronize.

Step 2: Find an Anchor Point (Or Two)

The next step is to identify an anchor where we can agree that one event is present simultaneously in both the 9-1-1 call and the silent video.

These are our anchor points, or the spots in our two different media that will allow us to then align the time and date. We will use our senses and simple documentation for this part.

For example, in ol' farter's case, the jingling on the door when he enters and leaves the store can be matched to the very clear visual of entering and leaving the store in the video, with the bells seen bouncing against it.

Let's say the 9-1-1 call came in at 11:00:00 AM, and at the 2-minute mark, the fart occurs. At the 2-minute 10-second mark in the audio, the jingle of the door can be heard as the culprit leaves. In the surveillance video, the door is shown opening with the bells moving at the 42:28 mark of the video.

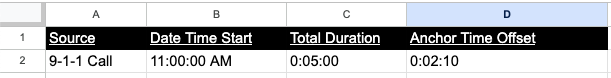

It can be useful to sketch a simple table to help keep track of everything, or if you are a gigantic nerd like me, just create a Google Sheet. We recall from the scenario above that the 9-1-1 call recording was 5 minutes long.

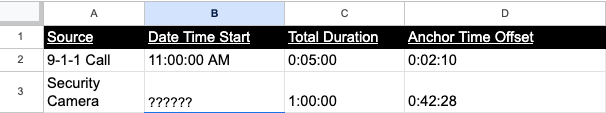

Now, if we extract the information from the video recording and apply the same approach, it will help us visualize what information we need to estimate. Recall that the surveillance video has no time or date on it and is an hour long.

To recap, on the 9-1-1 call, we can hear the door jingle on exit, and on the security camera footage, we can see the man exiting with the bells on the door bouncing.

Is this going to be millisecond-accurate? No, of course not, but it will be close enough for synchronizing these two things together. Unless you require Olympic-race-level, millisecond-resolution performance (good luck), it is perfectly acceptable.

Step 3: Applying Anchor Time to Synchronize Date & Time

Now, if we use a simple formula, we can begin to align the two media sources and apply a date and time to the video. First, because many of your media sources will have different durations, we need to establish the unknown start date and time of the video:

Unknown Date Time Start =

(Known Date Time Start + Anchor Time Offset)

-

Unknown Anchor Time Offset

Unknown Date Time Start = (11:00:00 + 00:02:10) - (00:42:28)

Unknown Date Time Start = (11:02:10) - (00:42:28)

Unknown Date Time Start = 10:19:42 AM

What we have just solved is that when you hear the door jingle in the 9-1-1 call at 11:02:10 AM, you can visually see the man pushing the door open and the bells moving. You also now know that the video, which is 55 minutes longer than the audio, started at 10:19:42 AM.

Now that you have anchored the two together, you can work in both directions. We know that at 00:02:10 of the 9-1-1 call, the offset is the same as 00:42:28 in the surveillance video.

So if you see something interesting in the video at 00:41:12 and you now want to know what is happening on the 9-1-1 call, you need to figure out what the offset is in the audio file. We can use a simple formula again:

9-1-1 Call Offset = (9-1-1 Anchor Time)

+

(Video Offset of New Event - Video Offset of Anchor Time)

9-1-1 Call Offset = (00:02:10) + (00:42:28-00:41:12)

9-1-1 Call Offset = (00:02:10) + (-0:01:16)

9-1-1 Call Offset = 00:00:54

As you can see, we can now zip our audio recording to 00:00:54, or just before that time, and hear the audio match what we are seeing.

Now, no matter which source you are working from, you can easily begin to figure out what date and time occurred, but you can also figure out the offsets or locations in multiple media files where that event happens at the same time.

The other cool thing is, of course, the 9-1-1 call is only 5 minutes long, but you have 1 hour of surveillance video—now with a date and timestamp that you can use throughout. It is not uncommon to have to stitch or stack together multiple media sources, as one may end and the next begins. You may also have various overlapping 9-1-1 calls that are happening in parallel. All of this becomes much more manageable as you look to find a source of time, anchor an event to it, and then use some simple math to synchronize each additional source to it.

Wrapping Up

Whew! A farting old man, math, who knew that Bullshit Hunting would be so gross and nerdy. I’m here to tell you, it really is gross and nerdy most days.

Now, there are numerous caveats and gotchas that I do want to leave you with. First off, it’s key to remember light travels much faster than sound. While this might not be applicable to cutting a fart in a fictional convenience store, it becomes very relevant during shootings. What you see in a video and what you might hear, and the timing of the two, can be very different; this is where using your senses is not enough. You need to corroborate with as many sources as possible to narrow it down further.

And corroboration is something you should be doing anyway.

As always, when working in an imperfect world, there is a part that is art and a part that is science in solving issues related to digital evidence. It is not about admissibility or rules of evidence, as you’ll note that I didn’t mention whether we were on the defence, the prosecution, or just a journalist. It’s because it didn’t matter. What does matter is that you are not avoiding diving into evidence because it may be a discombobbled, disorganized, spoliated mess.

By slowing down, using our senses, and methodically documenting the information we know, we can start bringing order to the chaos.

In my next instalment, I’ll teach you what I call the Metal Gear Solid video analysis technique using nothing more than your wits and Google Maps.

See ya next month!

A note from the editor (Kennedy): I hope you, like me, started this article with tense fingers and an eye-twitch, wondering what horrors await. A robbery? A kidnapping? A murder most foul? Not at Bullshit Hunting.