How to get in to Harvard

Step One: Die in 1888.

Two years ago, I wrote about Mary Tynan,1 a young woman who died in Boston in the late nineteenth century.

During the last decade of her life, Mary2 was cursed with a type of inconvenient fame — the kind that led to an obituary in the New York Times, but not, as far as I can tell, a dollar, a dime, or a moment of peace — because she was believed3 to be the surviving victim of the Boston Belfry Murderer, Thomas Piper.

As I was writing about Mary, I left something out.4 A yet-to-be proven something; one of those odd inferences that grows not from any single fact, or source, or statement, but from the general arrangement of facts, and the spaces between them. In other words, a funny feeling.

I thought.

Or rather, I felt.

Or rather, I began to wonder if5.

Harvard University had her skull.

I took a small scour around, before we published the piece two years ago.

But there was nothing listed in the few catalogs published of the Warren Anatomical Collection. There was no publicly available listing of items donated to Harvard University by Dr. Benjamin Cotting in 1897.6

So I set it all aside. For a while.

Until, roughly, Christmas. Of this year. No better time to solve a small mystery, bother a curator, or trouble a librarian. Or, in this case, all three at once.

The Warren Anatomical Museum7 is no more. The items which were once displayed are now part of “the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine.”

I sent off a little note, via an online form, and received this back from the curator:

Dear [my whole real name8],

Thank you for contacting the Center for the History of Medicine and your interest in the collection of the Warren Anatomical Museum. I’m happy to help as I can.

Working through the museum collections database and archive, I have not found any evidence that Mary Tynan’s remains were ever transferred to the Warren Anatomical Museum by Benjamin Cotting or another donor.

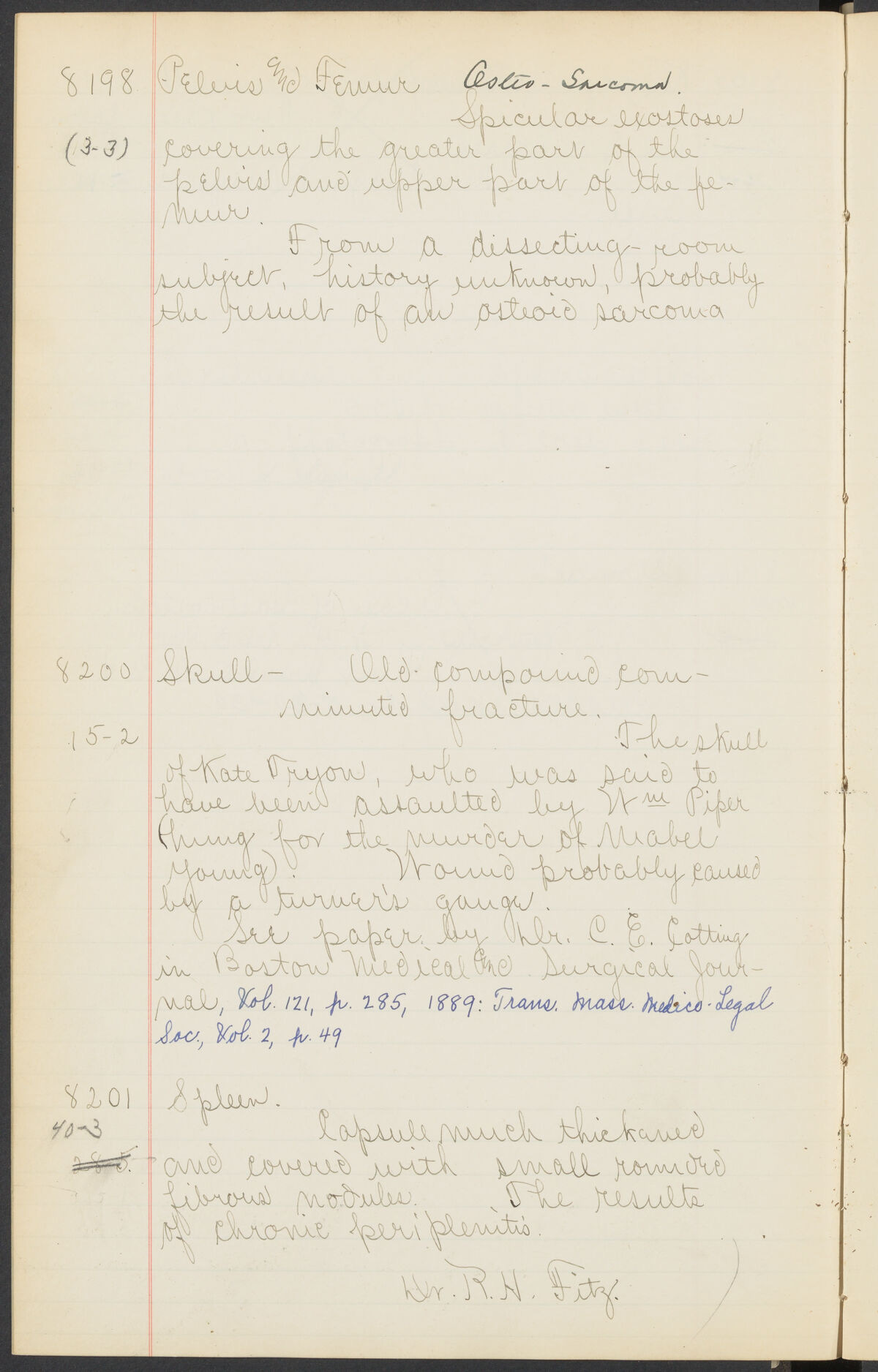

Mabel Young’s remains (skull) are still in the holdings of the Warren Anatomical Museum collection at the Center for the History of Medicine.

Of potential interest, the remains (skull) of another one of Piper’s possible victims, Kate Tryon, was donated to the Warren Anatomical Museum by Cotting. Tryon was assaulted and lived, and Piper later claimed the attack. Cotting believed that this confession was false. Those remains have not been seen in modernity but I can supply some archival information on the case should you be interested.

Was I interested?

I’d never been more interested, in anything. Ever9.

He sent me the following:

Harvard does not have Mary Tynan’s skull; Harvard has Kate Tryon’s skull.

Kate Tryon, who, per acession records above, was “said to have been assaulted by Mr. Piper, hung for the murder of Mabel Young” and died of a “wound probably caused by a turner’s gauge.”

Kate Tryon, who, oddly, is not mentioned in any contemporary newspaper accounts of Mr. Piper’s last confessions, which were covered, broadly, in the press.

Kate Tryon, who was — per birth, immigration, and death records — not born in, did not immigrate to, and did not die in, Suffolk County, Boston, between 1860 and 1890. Not as Kate, Catherine, Katherine, Kathryn, or Caitlin.

One wonders how two such similar women existed, in the same places, at the same time, one leaving paper, and the other, bones10.

Or Tyner, or Tyvnan.

Generally I don’t like the chumminess of calling crime victims by their first names, as if we are intimates; however, I can’t find a satisfactory or consistent spelling of her last name. Her first, however, with one notable exception, is always “Mary.”

Not by me.

Despite the unnecessary length of the deep dive into Emilie Russ, I swear to god I am capable of leaving things out.

A brief list of facts, from which I began to draw this “feeling:” Dr. Cotting was in possession of Mary’s skull while lecturing; he donated the skull of another victim of Thomas Piper’s to Harvard, which was displayed at the Warren Anatomical Museum; Mary’s burial place is not listed in death records.

It was also a less than ideal time to make idle inquiries into the treatment of human remains at Harvard.

When I was a child, I believed it was a museum of ghosts, and called it the “Spook Museum.”

When writing to curators, or librarians — just like you would with a freedom of information act request — it helps to use your whole, real, or real-seeming name. If I’d had an email address that ended in “.edu” I would have used that, too.

I am often more interested than I have ever been, in anything, ever. Precisely when the adderall wears off.

I am actually grateful to the curator at Countway for tolerating my inquiry; none of this is to be read as sarcasm. Different records, kept for different purposes, will often contain different kinds of information. There are many reasons for the museum records to be like this, and newspaper accounts to differ.

Working first in public defense and then removal defense in a public interest firm means that we in practice have to chase down records, evidence, even do cell tower triangulation and once, discovering that the local Walmart's "proprietary" video storage format was just XviD with a slight alteration in the file header (who said piracy doesn't teach anyone anything?) But the one case that I never figured out was one where a client found himself unable to prove his citizenship status despite living in Queens his entire life because he was born on an American Air Base in Germany to a single mother with LPR status. Father refused to legitimize, but that's fixable if we can show that he entered the country on a military flight with the mother and derive his citizenship from her's, which she has had since the late 80s.

Except as it turns out, there wasn't any proof of how he entered the US the one and only time. After a lot of calls I got to the National Archives who, after a long hold, told me that military transport records for a few air bases stateside covering the time when the flight took place were destroyed inadvertently. From a fire. While moving.

Not from the famous fires concerning the National Archives in 1973 and 1978 that is easily found on the news. All I needed was the passenger manifest for a military flight that had no issues and was entirely routine. The archivist, who sounded my age (late 20s at the time) and was apologetic, invited me to check the records, except I was in NY and I could barely take a lunch break, never mind trekking down on Amtrak for this. We didn't even have the budget to sign up for newspaper.com to search, atlhough that would've taken quite some time as well. It's entirely possible that the only person for whom these records mattered was the client but, well, that doesn't mean it's not a problem.

And why did he need this set of records almost 40 years after his birth? Because ICE had picked him up and destroyed the documentation he had and removed him to Mexico even though he spoke no Spanish and was left on his own knowing nobody. This didn't happen in the last year, this happened in 2014. He smuggled himself back after 6 months only to find that he is suddenly no longer able to show that he exists as a person, on paper. The law is contentious in edge cases and this was one hell of an edge case. We simply didn't have the resources to figure it out and really this still haunts me once in a while, especially today.

The person is absolutely real. He talks like my friends who grew up in Queens. He's a Mets fan. His mom is willing to draft an affidavit but that doesn't do anything. Procedures have changed a lot since the early 80s in all aspects of how immigration law is conducted, interpreted, and the bureaucracy arising out of it have become punitive and sadistic. Citizenship is a binary only insofar as those whose birth can be attested to with certainty or who naturalized with countless witnesses on hand. That leaves such a big gap from home births to Americans born overseas to American parents but not in proximity to consular services, or a million other edge cases that if one practices the more contentious areas of immigration law, will inevitably come up. The year you were born can be the most important determinating factor, but only to people born in a specific circumstance. Why can't America realistically have a nationwide database of all citizens? Constitution aside, because only courts can decide and the case law is complicated and really goes into the weeds. Many Americans each year in fact are deported not knowing that they are in fact American. There's also no definitive way to prove one's citizenship if one derives it from a parent. My college roommate is very much American - white kid, American parents, homeschooled but not unique at my college since 1% of kids went to a Sudbury Valley school. But he can't get his social security number, since he spent most of his life seasteading and didn't have the same set of docs the rest of us have, Eventually he had it sorted out, but if he was any shade of dark, had an accent, and didn't have wealthy but exccentric parents whose citizenship wasn't in doubt, could he? I have my doubts

This entry reminds me of a case I’m working, and I determined that researching the construction history of a particular logging road would be useful. I was able to get on the phone with a research librarian at the big state U library (the job opens doors) and she was able to provide me a wealth of information related to how that road was cut over decades.