Surveilling the State: Open Police Records

Using open records to highlight patterns of domestic and intimate partner violence.

The Canadian prairie provinces are home to the bulk of the team at Permanent Record Research—namely Saskatchewan and Manitoba. These two-bald-ass-bare provinces also have the dubious distinction of reliably topping the Canadian leaderboard in domestic and intimate partner violence rates.

In a report released on October 10, 20241, the number crunchers at Statistics Canada had this to say, “Among the provinces, Saskatchewan (741 victims of family violence and 710 victims of intimate partner violence per 100,000 population) and Manitoba (588 victims of family violence and 628 victims of intimate partner violence per 100,000 population) had the highest rates.”

This epidemic on the Prairies has stretched far enough in time to touch this author’s home and others on the Permanent Record Research’s team, a complex, multigenerational problem. One that we as a society are continuing to grapple with, and bungle.

Today, though, we’ll talk about a twin to the south: Oklahoma. The “twin” monicker is neither a compliment nor an insult, just an observation. The oft-quoted statistic in Oklahoma is that, “…it is estimated that 51.5% of Oklahoma women and 46.0% of men will experience sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner at some point in their lifetime.”2

It’s not just the victimization or homicide rates that are astounding. It is the incarceration rates of those who are victims of domestic violence. The myth of “stand your ground” is just that. Many women, and statistically less so, men, have either been coerced into committing a crime to benefit their abuser, been forced to defend their lives, or those of their children against their abuser, or have been connected to crimes their abuser committed, even though they had little to do with it.

And then they’re put in fucking prison.

We, Saskatchewanitobians? We get it. Truly.

We understand how fucked up a system is when it spends its resources punishing survivors of rape and domestic violence. So, it should come as no surprise that in the Fall of 2024, Permanent Record signed up as a volunteer investigator-Jane-of-all-trades to lend a hand to the leaders of the fight in Oklahoma: Oklahoma Appleseed Center for Law and Justice.

Oklahoma Appleseed

The Oklahoma Appleseed Center for Law and Justice was founded in 2022 by Colleen McCarty, the Centre’s current Executive Director and living force of nature. The organization is part of the Appleseed Network—19 justice centres spread across the US and Mexico that work to provide equal justice, reduce poverty and fight racism, and discrimination.

Oklahoma Appleseed wasted no time and quickly made a mark in their home state. In their three-year lifetime, they’ve published research on protection orders, prosecutorial misconduct, and produced an excellent podcast called Panic Button, which covers the case of April Wilkens—a domestic violence survivor and prisoner in Oklahoma.

Most notably, Oklahoma Appleseed fought ferociously to get the Oklahoma Survivor’s Act written into law in 2024. The Oklahoma Survivor’s Act of 2024, in Appleseed’s own words: “…provides a pathway for survivors of domestic violence and human trafficking to seek post-conviction relief when their trauma played a significant role in their crime.”3

There are a number of challenges from a research and investigations perspective when working on these cases. Many of them are decades old, and those that aren’t are frequently built on half-stories, half-investigations, and a lack of documentation. The age-old work of tracking down records, police files and witnesses—the shoe leather work—is what wins the day.

Thinking about paying us for a subscription?

Kindly consider a donation to Oklahoma Appleseed instead?

Just tap the wee button.

A Repeated Story.

A Repeat Offender?

There's a recurring theme in domestic violence cases where the police were called, often more than once, and yet, when re-reading the trial transcripts or reviewing records, the prosecution often disputes the number of times the victim reached out for help.

When someone has been re-victimized or gaslit by police or victims services, they stop making those calls. Despite what you believe, you'd likely do the same. Our job as researchers and investigators is to figure out if and when those calls happened and how they happened—play the hand we're dealt and all that.

It can seem daunting at first, but with a little bit of elbow grease and (of course) a spreadsheet, one can start challenging what's often incorrectly presented in Court regarding calls for police or emergency assistance.

It is here where open datasets can prove incredibly useful to the lawyer, paralegal, advocate or survivor. As part of a push for police transparency, particularly around gender and race, many police services across the United States publish rich datasets on their calls for service, arrests, traffic stops and criminal offences.

This is where labelling becomes essential for our use. A "call for service" is a phone call to the police or emergency services requesting the police or other emergency assistance. It does not mean a crime has been committed, nor does it mean that an entry into the police system will be made for a domestic abuser4. It is simply a record that emergency services were called to a particular address or area entered into the computer-aided dispatch (CAD) system.

The CAD system is a valuable resource in any investigation and should be something you are aware of when making public records requests. In some cities, this information is published publicly, and you can download it. In other cities, you will have to request it from the police, county or city themselves, and the systems will readily export to CSV or Excel-like spreadsheets.

Example Public Record Request:

I am seeking all calls for service from your Computer Aided Dispatch (CAD) system between January 1, 2019 and January 31, 2019. Please provide the information in CSV or Microsoft Excel format.

Here, we will be able to establish patterns of calls by a survivor, a neighbour or passerby, including any calls that may have been mislabelled to a nearby residence. The calls for service in most datasets will also include an incident or case number, which is incredibly useful for filing public records requests with the police, ambulance, fire or other emergency services.

We will use Norman, Oklahoma’s open data, which includes calls for service, offenses, and case information.

Download the 2016 dataset from here to follow along and quickly sort, filter and find the records you’re interested in. The same techniques will work across a number of police datasets in other locales such as Los Angeles5 and New Orleans6.

Loading Police Data into Google Sheets

Once you’ve downloaded your spreadsheet of data, you can head to: https://sheets.new to get a fresh Google Sheet started. If you are more comfortable in Microsoft Excel, then go on with your bad-spreadsheet-ass. Don’t let us stop you.

In the Google Sheets File menu select the Import option and then pick the Upload tab as shown below.

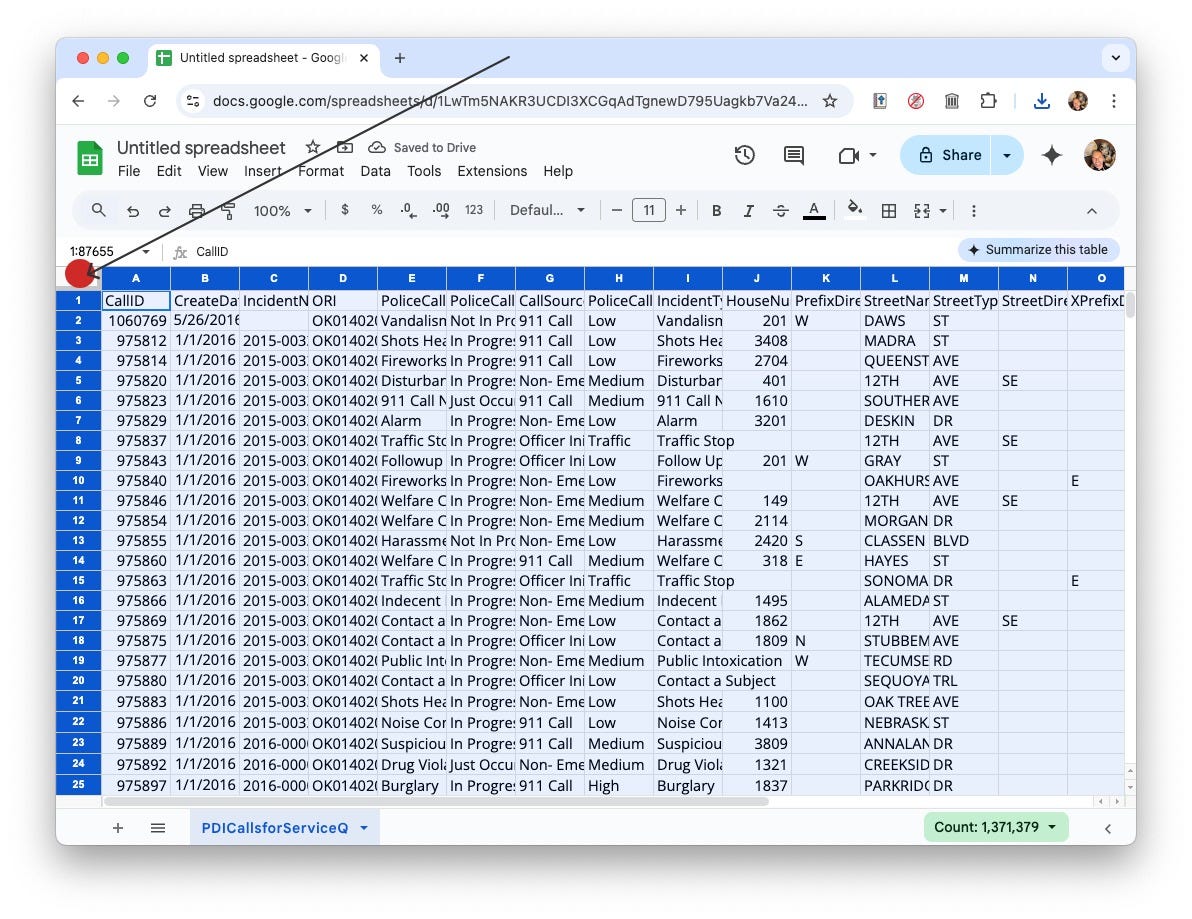

Once you’ve imported the Norman police data you should see your spreadsheet now crammed full of data, shown in the figure below, so the first thing we need to do is a bit of tidying. Click where the diagram indicates below. This will highlight the entire sheet for you as shown.

Now, two simple steps to format the data and provide us with some search and filter options.

Double-click the vertical line between the A and B columns. Give your browser a few seconds, and then it should have all of the columns automatically adjusted for width.

With all of the sheet highlighted, click the Data menu and then click Create a Filter from the menu. This will add little sorting arrows to the top row of your spreadsheet.

Perfect! Now we can simply click the PoliceCallType (column E) filter icon, and from the resulting list, only select domestic violence related calls. In the popup menu, first clear all of the options (1) and then use the search bar to search for “domestic” and select the resulting call for service type (2).

Now, you can either sort by date if your case happened on a certain day and area of town, or you can, for example, filter by StreetName which will give you all domestic calls for a street. You can then sort the column based on date or house number to look for patterns or your specific incident.

Here, I have selected a random street, then sorted on HouseNumber and we can see there is a repeated call for service, and three separate IncidentNumber values. If we were investigating this particular incident (which we are not), then we would immediately file for records from the Norman Police Department that would include the date and IncidentNumber.

You can try downloading other years, trying various forms of sorting and filtering, including adding more PoliceCallType fields to your filter. For example, if there was a resulting homicide or other crime that occurred, it’s often useful to include assaults in the list of fields.

Wrapping Up

Investigating domestic and intimate partner violence can be incredibly difficult, both from a mental perspective and a research perspective. It can be a heavy lift for each case: tracking down witnesses, finding out people have passed away, records have been destroyed or endless records requests that seem to go nowhere.

That doesn’t mean we just take the prosecution’s word when they say that there aren’t any records of previous calls that indicate a history of domestic violence. We should validate those statements with real data, where possible.

Even though this data sometimes appears unwieldy, even useless, with some patience and simple analysis techniques, the data can provide investigative leads and hard numbers to back up your casework.

Just because it’s hard doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be done. It doesn't mean we shouldn’t try.

Just ask Lisa Moss, who was released after 34 years for a crime she did not commit against an abuser who put her and her family through hell until he was killed.

A historic moment for Oklahoma. One of many more to come.

I hope I’ve given you a new tool to help the fight in your State, Province or wherever else this pandemic of violence has spread.

Statistics Canada (2023). Trends in police-reported family violence and intimate partner violence in Canada, 2023. Statcan.gc.ca. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/241024/dq241024b-eng.htm

October: Breaking the silence: Oklahoma’s fight against domestic violence. (2024). Oklahoma Attorney General (049). https://oklahoma.gov/oag/news/generally-speaking/2024/october-breaking-the-silence-oklahomas-fight-against-domestic-violence.html

The Appleseed Network. (2025, January 12). A Historic Victory for Justice in Oklahoma | Appleseed Foundation. Appleseed Foundation. https://appleseednetwork.org/a-historic-victory-for-justice-in-oklahoma/

This practice is sure odd when there’s ample evidence the police do enjoy a good gang database in the morning (See: Wichita, Kansas; Chicago, Illinois; and others ) - yet don’t seem to have the same lust for domestic abusers.

Data.gov - Data.gov Dataset. (2020). Tagged LAPD. Data.gov. https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/?tags=lapd

Policing Data - NOPD News. (2015). Nopdnews.com. https://nopdnews.com/transparency/policing-data/