The house that isn't there.

And how long it hasn’t been.

This is the third in a series on Commonwealth v. Russ. Prior installments are here and here.

On August 23, 1915, Emilie Russ was found strangled, with her throat cut, in the front room of a first-floor apartment at 178 Centre Street in Roxbury. Vina, her eleven-month old daughter, was found sleeping peacefully in the back bedroom, no more than thirty feet away. By August 25, 1915, Emilie’s husband, Oscar, was the only suspect, despite an airtight, acknowledged alibi.

The apartment was described as follows, by the Supreme Judicial Court:

A tenement of three rooms on the first floor of a six-tenement wooden house in Roxbury. The front room was a parlor or sitting room, back of which was the kitchen, and behind that a bedroom.

From elsewhere in the opinion, concerning the apartment:

That of the front room was locked from the inside and the one into the kitchen also was locked, having a Yale lock which fastened the door when it closed. … [Russ] entered the bedroom through a window by pushing aside a screen.

In the bedroom, [t]he clothing upon the bed was very much tossed. The baby was upon the bed at night and apparently had been there from the death of her mother until after the tragedy was discovered... It did not appear that any one had heard any sound from the child during the day.

[In the front room] the cold and lifeless body of the wife stretched on the floor between a couch and table. […] The clothing found on the body consisted of shoes and stockings, an undervest, a nightdress and kimono.1 […] There was no trace of any struggle in the tenement. Its furnishings were in order.

Neighbors testified that they didn’t hear anything from the first-floor apartment during the day.

How can we ever know what happened, inside a locked room, if we don’t know how big it was, what the doors were like, what the floors were like, how near the neighbors were, and what separated them.

God, I wanted a floorplan. Or a photograph. I’m not picky. I could make due with an elevation and maybe a quick hand on my knee, under the table.

A plot plan would hold me over. Or date built. Something.

Roxbury has no 178 Centre Street.

Neither building nor address exist as of 2025.

Suffolk County Registry of Deeds is only indexed back to the disco era, roughly, and the inspectional services department, although their records are scanned, searchable, and vast, works best with detailed information, like ward, precinct, and parcel.

Having none of these, I despaired.

As always when hitting a dead end, it helps to back up.

Go slow2. Reconsider. Try another angle.

When desperately lost, try a map.

Maps are like newspapers; now a bit of an oddity, almost an affectation, they were once pervasively ordinary, even a necessity of adult life, existing in flavors and detail that boggle the app-addled modern mind. And they persist.

Before drone flights, drive-by inspections, cheap photography and algorithms, fire insurance maps were once a critical tool for insurance underwriting. They showed building height, lot size, setback construction, materials, use, age. Distance from standpipes, hydrants, fire stations. The width of roads and their material. Useful stuff, for knowing as much as you can about a building and a neighborhood, from long, long ago.

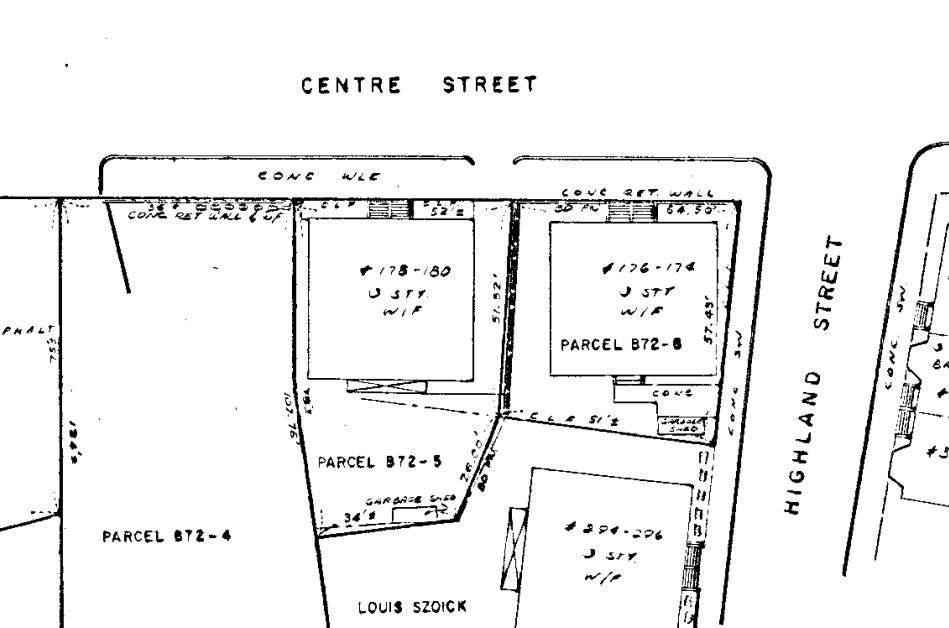

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find a fire insurance map for Roxbury between 1910 and 19203. I did, however, find an atlas.4 From the proper year, even.

A first glimpse at the last home of Emilie Russ.

178-180 Centre Street is the second yellow square in from Highland Street, on the plot labeled “Wildey Savings Bank.” Yellow buildings are wood-framed. Pink are brick. The tiny numbers indicate how many floors. Script identifies property owners.

If the house stood for fifty-four more years — and there’s reason to believe it did5 — it was demolished during the first phases of preparation for the never-built Southwest Expressway around 1969.6

Documents from the taking show a three-story wood-framed house, with stairs on either side of the wall dividing 178 and 180 Centre, and an abbreviated, perhaps, porch, on the back.

After the plan for a twelve-lane highway was abandoned, the land stood vacant for a time, until it became part of the Southwest Corridor Redevelopment Plan.7 Emilie Russ’ last home is now a parking lot, serving Roxbury Community College.

History, framing, and guesses.

Going backwards, to get a sense of age, the building appears in maps in 1906,8 1899,9 1890,10 and 1888,11 but not on one published in 188312. Older maps show the landowners as Lucius M. Sargent and Horace B. Sargent, Jr.13

Lewis Hine, documenting child labor and home work, photographed several homes on Centre, Highland, and Marcella Streets in 1912.14

If the house on Centre Street was similar — and based on the sketch in the takings plan, it very well might have been — it was a type that Northeastern Professor Peter H. Wiederspahn refers to as a “wood-frame row house.”

Prof. Wiederspahn describes their typical layout as follows:

Most wood frame row houses were approximately 30 feet deep, and each unit was between 18 to 24 feet wide. […] The three story row houses could either be a single-family, a two family, or a three family unit. The two and three family units have a single front door that leads to an internal common stair with a privatizing door at each level, and another external stair attached to a porch on the back.15

This description makes sense.

A back porch would have been required, for Oscar Russ to access the bedroom window to climb in. Steps were known to exist, because that’s where he waited, smoking, upon arrival home from work.

Three rooms back-to-back, with a hallway and stairwell between the apartment and the firewall, separating it from 180 Centre. Private stairs from a brief, common hall align with the court’s description of only two means of access into the front room, where Emilie was found: Via the locked door and kitchen.

But what was it like?

The Supreme Judicial Court called it a tenement; so did Oscar Russ’ attorney, Wendell P. Murray, in later writings.

I’m content with the description.

Not one of the airy double-parlor, front balcony/back porch, built-in cabinets and abundant means of egress three-families that survived to see their revival as condominiums, but something utilitarian. Front porchless.

Balloon frame, or mostly balloon. Lathe and plaster walls. Small rooms. Light entering from one side only. Running water to each floor, but possibly a shared toilet in the basement.16

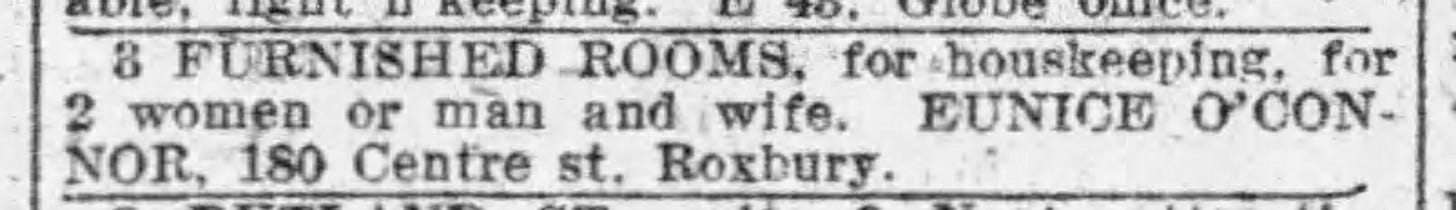

Emma F. O’Connor was identified in newspapers as the owner of 178 Centre St; she wasn’t. Like her father before her, she was an agent, a rent collector, a manager of tenements.

She placed the advertisement, below, in a Boston paper in 1909.

By 1915, Ms. O’Connor was a single17 woman, head of a household, consisting of herself, her brother, sister-in-law, niece, and nephews. Ms. O’Connor lived at 180 Centre from 1890 to her death in 1919, leasing the building next door — and likely, the seven other tenements on the corner of Centre and Highland — to tenants, like Oscar and Emilie Russ.

The advertisement, below, ran in the Boston Globe in May of 1915:

Census records indicate that 180 Centre, which shared a firewall with 178, was consistently — and solely — occupied by the O’Connor family, while 178 typically housed three or more households.

Descriptions of the case mostly omit mention of the more prosperous family, occupying the three floors next to 178 Centre.

Best-laid plans of mice and men: Occasionally inaccurate and rarely drawn to scale.

By means to be discussed in a subsequent post, I did obtain something purporting to be a floor plan based on one entered into evidence at trial.

Yet I still went through all of the above, and yet more I have not outlined because, frankly, I like this source. I love this source. I am fully charmed by it and delighted with myself for finding it, but I can’t trust it.

I wish I could.

Forensic and medical testimony concerning the condition of the body will be discussed in a subsequent post.

I wanted to type “go slow and use a lot of lube,” but today I am feeling fancy, and not writing about butt stuff. I am writing about very serious property records and diligent searches, etc. Zero butts.

There is one for 1888, however; 178 Centre is there, wood-frame. Second house in from Highland Street.

178-180 Centre Street appears to still be standing when the Order of Taking was recorded at Suffolk Registry of Deeds, Book 8301, Page 120, July 9, 1969.

However, I located no building, demolition, or alteration permits from 1880 to 1969, with the Department of Inspectional Services. I also found no evidence that the building burnt down or was damaged by fire in the interim.

It’s fair to guess that the building demolished in the 1960s was the same one, at least in a ship-of-theseus kind of way, as the one where Emilie Russ died; can I guarantee it? No.

First big leg of inner belt set to go, Boston Sunday Globe, April 27, 1969.

The “Southwest Corridor” is an interesting story, with aspects that, compared to present, feel almost hopeful. See Plot 35. Also see this brief pamphlet on the history of the Highland Park Neighborhood.

Sons of Horace Binney Sargent.

Photos taken within a few blocks of the Russ home, in 1912: Pritchard family, 293 1/2 Highland Street, around the corner, across the street; Dolan Family, 279 Highland Street, a few doors down from the Pritchards, 251-253 Highland Street, a bit further down Highland, on the corner; 88 Marcella Street; Highland Street, behind 178-180 Centre; interior, 268 Centre, a few blocks away, past the intersection with Lamartine Street.

This fantastic paper by a Prof. Weiderspahn, a gentleman I do not know, is very worth a read.

New England homes, older ones, often have defunct toilets in the basement, despite consolidating “toilet” and “bathroom” on an upper floor. Conventional wisdom was to leave them there, as one would rather that sewage backed up into the basement than the kitchen sink.

Or possibly divorced. Emma O’Connor was described once, as an actress; she also may have very briefly run 178 Centre as a a kind of speakeasy. She was arrested and charged with doing so, at least, in 1891.